In this post I go through Kusto Query Language – A very powerful querying tool used by Azure Data Explorer and Log Analytics Workspace’s.

Why I learnt KQL

I learnt KQL because I work at a company which uses Microsoft Sentinel, a powerful SIEM tool, which is actually built of an Azure log analytics workspace (Which is built of ADX). SIEM stands for Security Information Event Management – Where are the events stored? Well a log analytics workspace of course!

A quick introduction

Below is a query which checks the SecurityEvent table for events which match the Event ID of ‘4625’ (A failed login)

SecurityEvent

| where EventID == 4625This 2 line query will search the entire Log Analytics Workspace for failed logons. If all your machines are sending logs to the Log Analytics Workspace, you will see every single failed login. “But what if I want to search for a log from a single computer” I hear you asking, you can just add the following line. The ‘SecurityEvent’ is the name of the table (Often referred to as a log source) we are querying the logs from. Any line after that must begin with the ‘|’ (Pipe) symbol.

SecurityEvent

| where Computer == "Computer.azureenvisoned.com"

| where EventID == 4625When constructing a query in KQL It is common practice to prioritize filtering criteria based on the order of their occurrence in the query. Beginning the query with filtering by the Computer name, such as “Computer == ‘Computer.azureenvisoned.com’”, before specifying the EventID, is done intentionally. KQL processes queries line by line, applying filters sequentially. By first filtering on the Computer name, we narrow down the dataset to only those events originating from the specified computer. This initial filtering reduces the volume of data that subsequent operations which is needed to process, optimizing the query performance. Basically – You want to narrow down the filters as quickly as you can to make your queries run faster.

Get started with KQL for free

If your interested in KQL, but don’t want to invest in a log analytics workspace or invest in an Azure account, you can setup a free ADX Cluster here. Follow the guide to set up your free Cluster, and you should see something which looks like this

Let’s have some fun with logs

I’m going to have a look at the ‘AuthenticationEvents’ table as quite frankly – It’s the most interesting.

The first query I’m going to write is very simple:

AuthenticationEvents

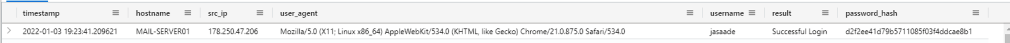

| take 100This just gets 100 different events, not in any sort of particular order. It’s typically a nice easy way to just have a general look at what the table looks like. The reason why I add the ‘take 100’ is because otherwise it will get up to thirty thousand logs which can take a while, and there is no need to get that many logs. Here is a sample log for people who aren’t following along.

The username for this log is “jasaade”, say I wanted to get all logon events for this user, I would do

AuthenticationEvents

| where username == "jasaade"

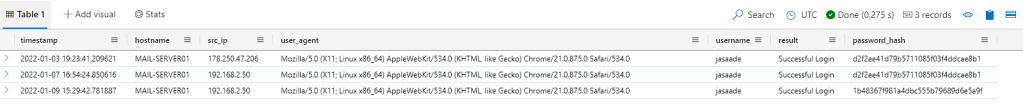

You can see the there is 3 events for this user, you can see this from the logs displayed and from the ‘3 records’ section on the top right. If I just wanted to get the amount of logs, plane and simple, I could add a ‘| count’ in a new line, which will just return the count.

Let’s instead get the amount of logins per user, to do this, we will be the summarize operator, followed by the ‘sort’ operator.

AuthenticationEvents

| summarize count() by username // Gets the counter per user

| sort by count_ desc // Sorts by count in descending order

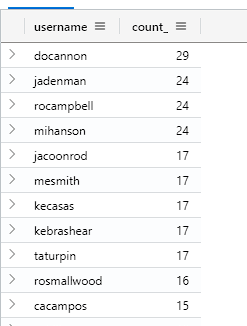

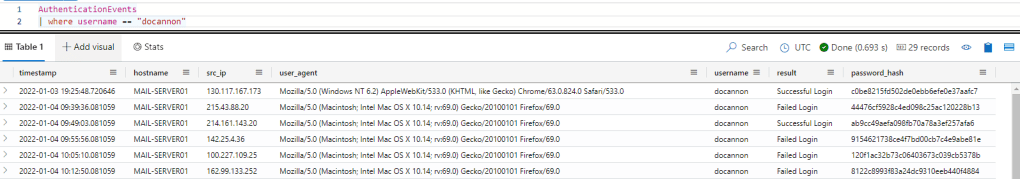

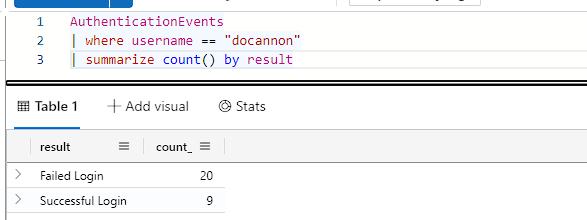

I can see that there is 29 authentication events for ‘docannon’, let’s have a look at his logins.

Here you can see he’s had unsuccessful and successful logins, let’s see how many successful logins vs unsuccessful logins he’s had.

Wow, quite a lot of failed logins!

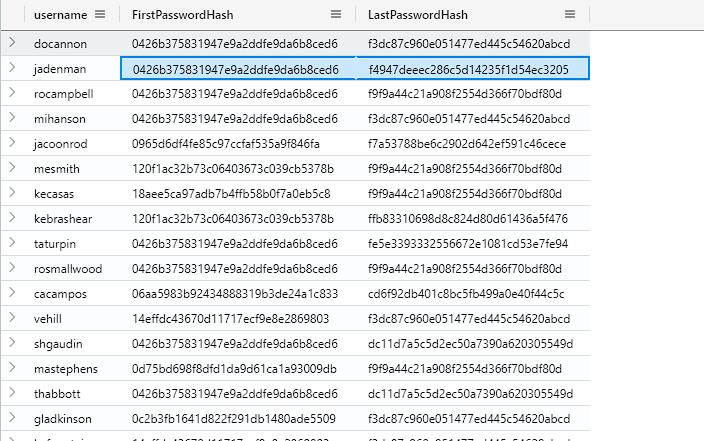

Say you wanted to get a list of all the users who’ve changed there password, we could do this by seeing if a password hash has ever changed. Easiest way of doing this is to get the min() and max() of the password hash, this gets the first log and the last log, we can then compare if the password hash has changed at all.

AuthenticationEvents

| summarize FirstPasswordHash = min(password_hash), LastPasswordHash = max(password_hash) by username

| where FirstPasswordHash != LastPasswordHash

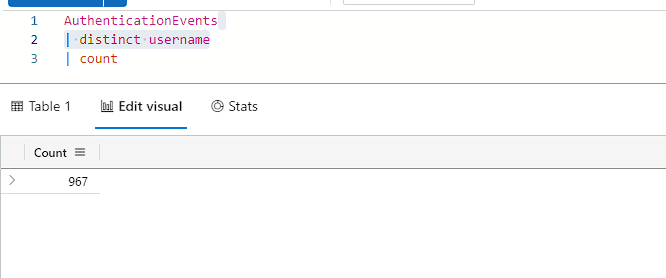

Here we can see quite a lot of users have changed there password. In fact, there is 757 different users who have changed there password. But how many user’s are there? We can check this by using the ‘distinct’ operator, followed by a count.

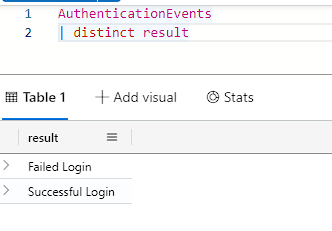

I often find distinct to be most useful to get a general overview of a heading, I’d use something like the query below if I was not sure what each output if ‘result’ may be.

Now, I could use the ‘summarize count’ like we did earlier, but this is easier and runs faster.

The last thing I’m going to show you is seeing if multiple users have the same password. I will first say that typically passwords are hashed and salted, meaning that even if users have the same password, the hashes wont match (This isn’t the case for this table). For this, I am going to use the arg_max operator, which gets the most up to date log (timestamp) by each user. Then we are going to get a count of each password hash and sort it from high to low.

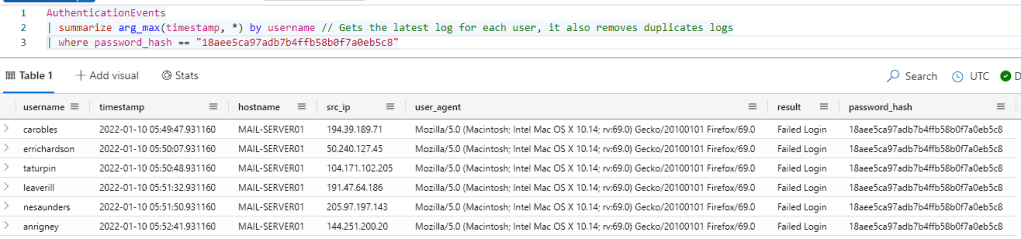

AuthenticationEvents

| summarize arg_max(timestamp, *) by username // Gets the latest log for each user, it also removes duplicates logs

| summarize count() by password_hash // Summarize by the count of password_hash's

| sort by count_ desc // Sort by high to low

Wow, we can see that 6 different users are using the password hash ’18aee5ca97adb7b4ffb58b0f7a0eb5c8′, Let’s run another query to see who these users are.

That comes to the end of my quick introduction to KQL, If you’d like to learn more I’d recommend looking at Microsoft’s documentation and listening to John Savill’s KQL overview

If you have any questions, feel free to leave them in the comment section below.

Leave a comment